A rare window into the early American monetary history — thanks to techniques from physics

Benjamin Franklin’s most famous inventions are the bifocals (also known as bifocals) and the lightning-rod, but a research group from the University of Notre Dame suggests he is also known for the innovative ways he made money.

Franklin, during his lifetime, printed more than 2,500,000 notes of money for the American Colonies, using techniques that researchers have deemed to be very original. The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, this week.

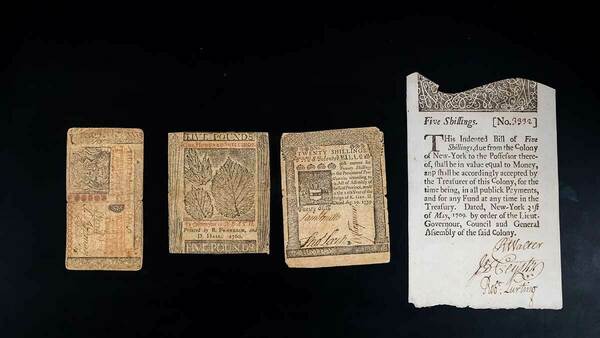

The research team, led by Khachatur Manukyan, an associate research professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, has spent the past seven years analyzing a trove of nearly 600 notes from the Colonial period, which is part of an extensive collection developed by the Hesburgh Libraries’ Rare Books and Special Collections. The Colonial notes span an 80-year period and include notes printed by Franklin’s network of printing shops and other printers, as well as a series of counterfeit notes.

Manukyan said that Franklin was not only a printer, but also a statesman. He wanted to help print money to support the fledgling Colonial currency system.

“Benjamin Franklin saw that the Colonies’ financial independence was necessary for their political independence. Most of the silver and gold coins brought to the British American colonies were rapidly drained away to pay for manufactured goods imported from abroad, leaving the Colonies without sufficient monetary supply to expand their economy,” Manukyan said.

The counterfeiting of paper money was a major obstacle to the printing of paper currency. Franklin opened his first printing house in 1728. At that time, paper money was an entirely new concept. Unlike gold and silver, paper money’s lack of intrinsic value meant it was constantly at risk of depreciating. There were no standardized notes in Colonial times, so counterfeiters could pass off fakes as genuine bills. Franklin developed a set of security features in his bills to distinguish them.

“To maintain the notes’ dependability, Franklin had to stay a step ahead of counterfeiters,” said Manukyan. “But the ledger where we know he recorded these printing decisions and methods has been lost to history. Using the techniques of physics, we have been able to restore, in part, some of what that record would have shown.”

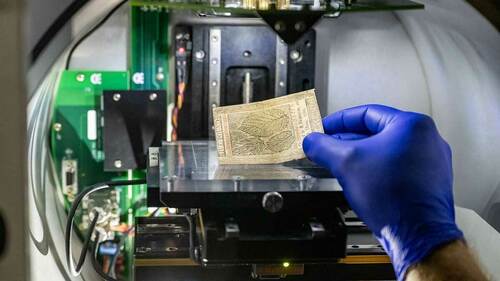

Manukyan and team used cutting-edge spectroscopic and image instruments located in the Nuclear Science Laboratory and Notre Dame’s four research core facilities, including the Center for Environmental Science and Technology (CEST), the Integrated Imaging Facility (IIF), the Materials Characterization Facility and Molecular Structure Facility. The tools enabled them to get a closer look than ever at the inks, paper and fibers that made Franklin’s bills distinctive and hard to replicate.

One of the most distinctive features they found was in Franklin’s pigments. Manukyan and his team determined the chemical elements used for each item in Notre Dame’s collection of Colonial notes. They found that the counterfeits had high amounts of calcium andphosphorus. These elements were only found in trace quantities in genuine bills.

Their analyses revealed that although Franklin used (and sold) “lamp black,” a pigment created by burning vegetable oils, for most printing, Franklin’s printed currency used a special black dye made from graphite found in rock. This pigment is also different from the “bone black” made from burned bone, which was favored both by counterfeiters and by those outside Franklin’s network of printing houses.

Another of Franklin’s innovations was in the paper itself. The invention of including tiny fibers in paper pulp — visible as pigmented squiggles within paper money — has often been credited to paper manufacturer Zenas Marshall Crane, who introduced this practice in 1844. Manukyan, along with his team, found that Franklin included colored silks into his paper much earlier.

The team also discovered that notes printed by Franklin’s network have a distinctive look due to the addition of a translucent material they identified as muscovite. The team found that Franklin started adding muscovite in his papers, and the size of these muscovite crystalline particles increased over time. The team believes that Franklin added muscovite initially to make printed notes more durable, but continued adding it after it was found to be an effective deterrent against counterfeiters.

Manukyan noted that working with rare materials and archival material is unusual in a physics laboratory, and presented special challenges.

“Few scientists are interested in working with materials like these. Some of these bills are unique. They need to be handled with extreme caution and can’t be damaged. Those are constraints that would turn many physicists off to a project like this,” he said.

The project, for him, is a testimony to the importance of interdisciplinarity.

“We were fortunate to have student researchers on this project with interests both in physics as well as in history and art conservation. Rare Books and Special Collections, the core research facility and the team of researchers were all excellent partners in the research. Without an uncommon level of collaboration across disciplines, our discoveries would not have been possible.”

In addition to lead investigator Manukyan, the research team for this project included Armenuhi Yeghishyan, a laboratory technician in the Department of Physics and Astronomy; Ani Aprahamian, the Frank M. Freimann Professor of Physics and concurrent professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry; Louis Jordan, an associate University librarian emeritus for academic services and collections; Michael Kurkowski, a former undergraduate researcher studying physics and mathematics; Mark Raddell, a former undergraduate researcher studying finance and physics who is now a consultant at Deloitte; Laura Richter Le, a former undergraduate researcher who is now a graduate student at the Conservation Center at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts; Zachary D. Schultz, a former associate professor at Notre Dame who is now a faculty member at the Ohio State University; Liam Spillane, who works at Gatan Inc.; and Michael Wiescher, the Frank M. Freimann Professor of Physics.

The project was funded internally by Notre Dame Research. For more information on the Nuclear Science Laboratory’s work investigating historical materials, visit sites.nd.edu/kmanukyan/research/.

Contact: Jessica Sieff, associate director, media relations, 574-631-3933, [email protected]